Why CHRONOLOGIES?

About the identity of the newsletter

Making research and writing a career involves the same challenges faced in many other professions. It takes time to train and work enough to build a voice, find yourself in your craft, and position yourself — and most of this process happens anonymously and in solitude. Anyone working with research (especially in the humanities) knows that, if someone could observe their routine from the outside, most of the effort would boil down to the monotonous scene of a person sitting at a desk, reading and writing for hours.

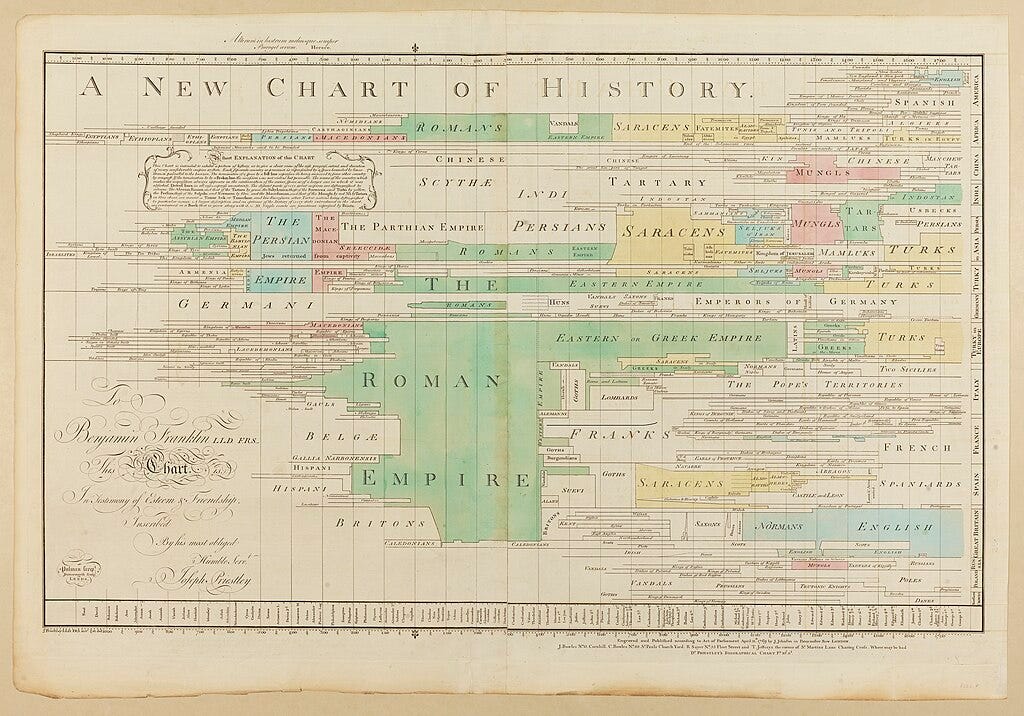

For some people, it is from this effort that the need to make sparks of research public emerges — whether to exercise the habit of writing, test the viability of certain ideas, or simply overcome the fear of criticism. It was from this need to bring private reflections into the public sphere that the CHRONOLOGIES newsletter was born (In this sense, this will be a newsletter with footnotes — but I promise there won’t be many!). As a historian, the name seemed, at first, like an obvious choice: if this space is dedicated to reflecting on the importance of looking at the past in order to understand the problems of the present, nothing could be more fitting than a name that conveys the idea of putting the past’s mess into order. However, the name CHRONOLOGIES turned out to be deeper than the initial obviousness suggested.

Since the early days of my academic journey, my research has focused on the field of Early Modern History. From the Renaissance to the Enlightenment, my readings and academic and popular science publications have been dedicated to themes related to religion, politics, and culture from this period. The choice of CHRONOLOGIES, therefore, reflects a consistency with this trajectory — since, among scholars of modernity, the discipline of chronology was considered one of the “eyes of History.” Alongside geography, it aimed to organize and give meaning to the past through the critical study of classical sources.1

The theme of returning to the classics also refers to a final characteristic of the identity of the newsletter. The interpretation of primary sources from antiquity, a distinctly humanist practice, had two main objectives. The first was historical: understanding that cultural artifacts from Rome, Greece, or the East were produced in different contexts required the development of critical tools to analyze these artifacts and their audiences, and chronology was one of these tools. The second objective concerned the purpose of this task. For humanists, critically understanding the otherness of the past was a way to, for example, interpret the rhetoric of a text in a manner that opened doors for philosophical reflection.2 Thus, the study of the past was not limited to satisfying curiosity but was conceived as a practice of “healing the soul.”3

Humanism began as a syllabus, but soon individuals trained in this curriculum created intellectual circles in which scholarship would become the tool for the “healing of the soul” in its entirety, with the classics serving as the source for the restoration of humanity — both individually and collectively. However, which classical sources would be used as references? In an attempt to answer this question, humanism divided into at least three fronts: Platonic humanism, Hermetic humanism, and Christian humanism.

Christian humanism has always caught my attention. Its difference in relation to other humanist groups did not lie in a distinct curriculum, but in the sources and concepts considered fundamental for humanist studies to restore the “humanity” of those venturing into the classics. Central doctrines of Christianity, such as the incarnation of God through Jesus Christ and the notion that every human being is the Image of God, contributed to the vision of humanity that was sought to be restored through study. Another important doctrine, that of divine providence, led the reformer John Calvin (1509–1564) to assert that no Christian should reject “noble and worthy” knowledge, whether proclaimed by brothers in faith or by unbelievers.4

This does not mean, however, that the crucial classical source for Christian humanism — the Bible — was interpreted uncritically:

These men used history and philology to prove the uniqueness of Christianity and the soundness of the Bible, not to conflate all texts and dispensations. They disliked […] dissolution of historical boundaries as much as […] dissolution of Revelation.5

It is clear that a “critical reading of the Bible” did not operate in the same way for everyone (as we will see in future reflections), but the idea that the pursuit of truth is driven by a commitment of faith — and that the encounter with truth shapes one’s understanding of faith — has always captivated me. As I wrote in my introduction, “the words of men are not the Word of God,” and the endeavor of Christian humanists was to better understand the boundaries between the two, supported by a carefully planned curriculum of study. As a Protestant Christian myself, reading about these Christian humanists gave me direction for my own scholarly journey: it is possible to be a Christian researcher who not only talks about religion, but also speaks from a place of religious experience and to a religious audience.

This, then, is the identity of CHRONOLOGIES: a space born from the interweaving of academic historical research and reflections that emerge from the dialogue between faith and reason. This publication walks with its eyes turned toward the past, not out of nostalgia, but out of the conviction that yesterday sheds light on today — and, perhaps, gestures toward tomorrow. Here, faith and reason do not cancel each other out, but question each other; history and theology do not compete for space, but invite each other into attentive listening.

The humanist tradition that inspires this project viewed study as a form of healing — not of bodily wounds, but of the soul, of perception, of judgment. May CHRONOLOGIES offer, to those who follow it, not ready-made answers, but the quiet delight of good questions; not the rush of information, but the depth of understanding. May each post help expand horizons, sharpen sensibilities, and cultivate inquiry — always with the desire to share what is learned in the silence of study with those who also seek to better understand the world and themselves.

Welcome to this journey!

Anthony Grafton, Defenders of the Text: The Traditions of Scholarship in an Age of Science, 1450-1800 (Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1991), 104–5.

Nicholas Wolterstorff, “The Christian Humanism of John Calvin”, in Re-envisioning Christian Humanism (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2017), 80.

Eugenio Garin, L’Umanesimo italiano. Filosofia e vita civile nel Rinascimento (Roma: Laterza, 1986), 29–30.

David Lyle Jeffrey, “Scripture in the Studium and the Rise of the Humanities”, in Re-envisioning Christian Humanism (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2017), 170.

Grafton, Defenders of the Text: The Traditions of Scholarship in an Age of Science, 1450-1800, 19.